Observing under a good astronomical seeing is the main problem of the planetary imager… much more than cameras’ settings or the correct use of softwares! Here are five meteorological conditions easy to catch that favors the sky’s steadiness.

Predicting a good astronomical seeing is a very difficult exercise, and under the stars we regularly have surprises – good or bad. I have no ambition here to write a complete study ;) but to share my experience about five meteo conditions that usually brought me good seeing over the years. Of course, you are not living in France and you may live as well in conditions different than mine (in a lowland close to the ocean). But you may be concerned with some of these cases.

1) Oceanic winds with high pressure

It must no be true even for the whole French territory, but if ever you live close to the sea whatever is you country (up to 200 to 300 km inside the land), I believe you’re likely to benefit from it as well. The good seeing is brought here by weak and undisturbed winds coming from the sea.

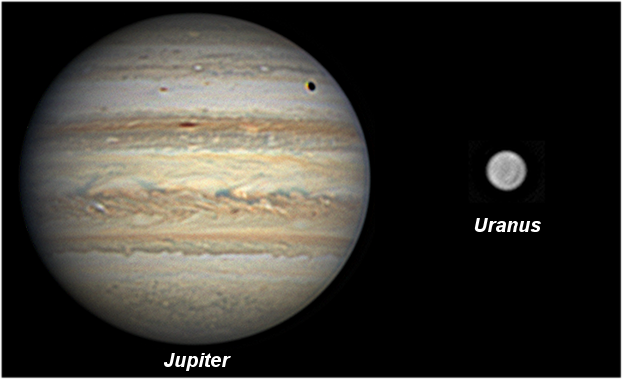

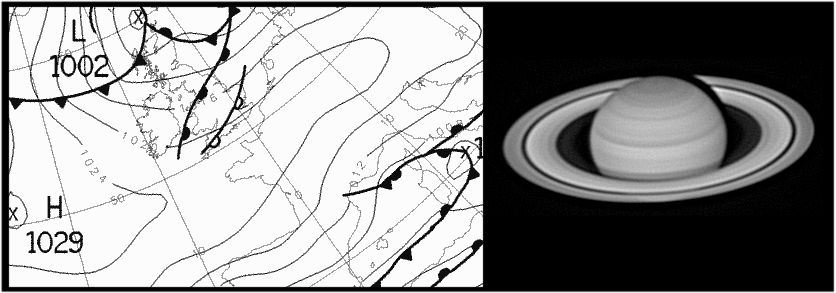

At left one example of the night from 15 to 16 September 2012 (GFS archives). A high pressure grew up on the Atlantic ocean and progressively drifted above the European western countries. As it rotates counterclockwise, on the French western coast where I live, the winds turned to west. Beneath the pressure map is a simulation of the jet-stream: it is not at its weakest, but it’s directly coming from the ocean. That night the steadiness of Uranus on the laptop screen was unbelievable, and the image taken with the Baader RG610 filter shows the equatorial and north polar belt. The seeing was still excellent a few hours later to image Jupiter. Images taken in Nantes with a 250 mm gregorian and a PLA-Mx camera.

2) The thermal inversion

Some says that the fogs favors good seeing for planetary observations. In reality the fog has no role here, but it is itself a consequence of the situation that is responsible for this kind of steady sky: the thermal inversion.

Under a normal situation in our atmosphere, the temperature decreases with altitude. This rule might invert under certain conditions when a strong high pressure (HP) stays for long above our heads: the temperature above a given altitude is greater than the one found just over the ground. Because convection has stopped (the ground air is not allowed to rise anymore), the atmosphere is very steady and gives excellent telescopic images.

Unfortunately, the inversion is often accompanied by fog… this is of no consequence if it remains faint, but fog can easily thicken by the hour and it might end obstructing completely the view.

The fog forms because the humidity trapped over the ground under the inversion layer condensates. It can do so more easily if the temperature is low, this is why we are going to see it more often during the cold season in fall or winter. Sometimes true blocking highs can happen, when a strong HP stays during several days, preventing fronts to reach the country. In this situation a persistent thick fog is much likely to form in winter.

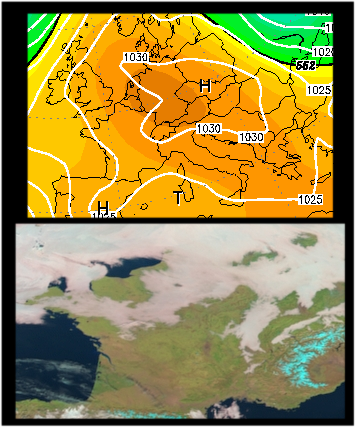

At left, blocking highs over western Europe in 2004 December, with huge fogged areas over northern France, that do not shrink during the day but keep growing at night. Images GFS and Meteosat.

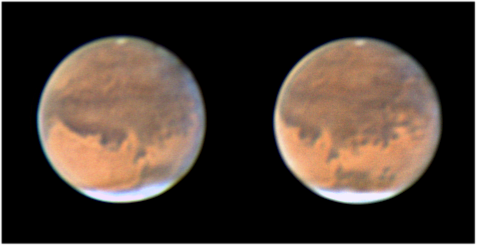

Beneath, Mars images taken on November 18th, 2005, under a thermal inversion. The seeing was excellent, but the sky transparency began to plummet already around 10/11H PM. For the second image secured just after local midnight, the frame rate of the camera had to be divided by two. On the next day the thick fog was there and for a week or so. Images taken in Paris with a Mewlon 210 and a Lumenera 075M.

3) The passage of anticyclonic ridges

3) The passage of anticyclonic ridges

The arrival of a High pressure over you is not always a guaranty of good astronomical seeing – this is more complicated than that. However there is one situation that looks to favors more regularly steady skies: the passage of an anticyclonic ridge.

A ridge is an elongated region of a high pressure center that passes over your country while the HP itself remains where it is (for France it will remain above the Atlantic). This is a temporary phenomenon and in France it brings a similar situation to the first one above: oceanic weaker winds. The jet-stream is forced to get around it.

Here is an example of the night from February 28th to March 1st, 2005 (map from MetOffice). The ridge was coming from the north while a strong HP center was descending from Island (during a cold wave). The view of the Cassini division inside Saturn’s rings, perfectly figured, was fascinating. Taken in Paris with a Mewlon 210 and an ATK-1HS (click for full size).

Of course the passage takes only a few hours so the timing is important: you may see it during the day and the next night will get cloudy again…

4) Dawn and twilight

One phenomenon that disturbs the atmosphere is convection. Warmer air masses rise and cooler ones go down. Well the convection

It happens of course during the first three “good conditions” but I have seen it sometimes even when the seeing was poor at night.

At right, Jupiter taken at dawn on August 12th, 2012. The sky brightens the blue component… 250 mm gregorian and PLA-Mx camera.

5) Before a cold front

Another good situation that is well known from observer are the hours that precedes the arrival of a cold front. The front is the limit between an incoming cold air mass and a warmer air mass. The cooler air trailed by the front lift the warm air (because it is more lightweight). There is then an inversion phenomenon with similar effects as those described in point 2): the convection stops and the seeing improves.

The interest of looking for the arrival of cold fronts may differ quite a lot from where you live. At my location I do not follow them because the front is rarely preceded by clear skies. But I know that in the United States it looks to be recognized as one of the major factor of good astronomical seeing, probably because cold fronts arriving from the north west travel over the land and are less cloudy than those heading toward France, that cross the Atlantic ocean, gathering humidity.

1 Comment

Interesting to know about temperature inversion and cold front passage but also about the advantageous dawn and twilight effects. Thanks for your information, very much appreciated!